When a new baby is born in China, he or she gets a name that no other person known to the parents has. The name is a combination of words or radicals that have a meaning, which the parents believe to be ideal for the baby. What an ideal name is like will be discussed later in this article.

A lexical category of names has not developed in Mandarin Chinese for the simple reason that the so called “name taboo” forbids the same name to be used more than once. Thus a Chinese proper name can be identified as a name only in a context; unlike words such as Marie or Thomas which in western cultures are immediately understood as proper names.

A further fascinating fact is that a Chinese person may have quite a few different names that are used in different contexts. The so call called “milk name” is used in the family and by close friends; the so called “official name” for official purposes. An artist may have more than one pen names and a distinguished older person a so called “respect name”. People, who deal with foreigners, take an English, Russian or German name to make communication easier. All this suggests that the self-identification of a Chinese person does not depend on his name to the same extend as it does in western cultures.

Chinese names have always fascinated me, because they seem so rich in meaning and aesthetical values; they look like paintings, have a musical tone and they seem to carry a great deal of symbolic content. Such names are comprehensive symbols, which can be perceived with all the senses: they are visual and auditory and they can be smelled and even tasted.

Think of a little girl, who calls herself 香花 Xiāng Huā “fragrant flower”. A lovely name makes the lady lovely.

Perhaps her name is 香花 Xiāng Huā “fragrant flower”.

Perhaps her name is 香花 Xiāng Huā “fragrant flower”.

康有为 Kāng Yǒuwéi “a promising, active and productive person”.

康有为 Kāng Yǒuwéi “a promising, active and productive person”.

康有为 Kāng Yǒuwéi was a Chinese scholar, noted calligrapher and prominent political thinker and reformer of the late Qing Dynasty (Wikipedia). His name could be translated as “one who is promising, active and productive“. A powerful name makes the man powerful.

When naming a baby the parents often express their wishes for the future life of the child. They also may express their own wishes like the one of having a son, when they call their daughter 带弟 Dài Dì “bring little brother”.

I believe that people in western cultures often tend to measure a great importance to the symbolic meaning of Chinese names. The symbolism of a name is interesting to us because it is often missing in our own names. We seldom know where our names come from or what they mean. The historical origin and the etymology of western names seem not to bear great significance in modern times. Another important, but not so obvious, aspect of a Chinese name is the information the name may contain about the social background of its carrier.

I wrote my second Bachelor’s paper on Chinese names. If you’d like to read the whole text, here is the link A Chinese Name is an Act of Creation

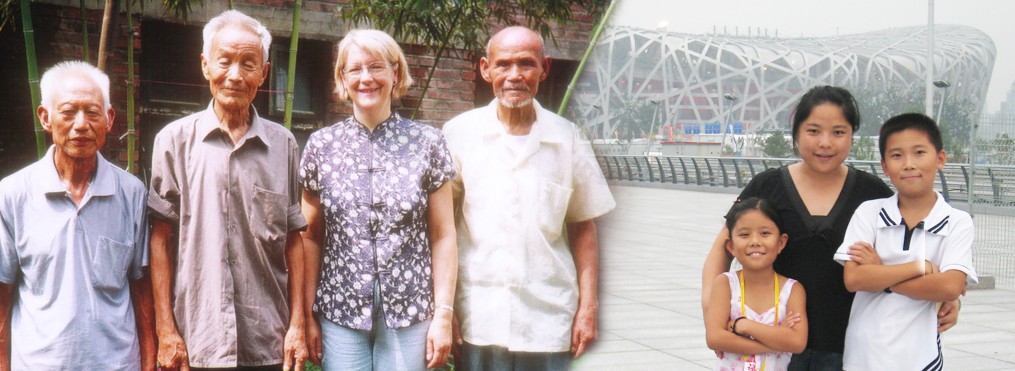

For my German speaking readers here is a link to an article of mine that was published just before the Olympic Games in Beijing 2008 Der Bund Artikel Namen . Scroll down the page to find my article.

康有为 Kāng Yǒuwéi “a promising, active and productive person”.

康有为 Kāng Yǒuwéi “a promising, active and productive person”.